# The Illusions of Knowledge: Understanding Cognitive Biases

Written on

Chapter 1: The Quest for Truth

In the realm of science, our goal is to seek objective truth—more engaging, more comprehensible truths. Certainty is often elusive. As Karl Popper insightfully noted, understanding that human knowledge is inherently imperfect leads us to acknowledge that we may never be entirely free from error.

In today’s world, we find ourselves inundated with vast amounts of data and information, both accurate and misleading. It is essential to cultivate critical thinking skills to distinguish between reality and falsehood. The human brain, a remarkable product of evolution, excels at complex reasoning but is equally adept at self-deception.

The Overestimation of Knowledge

In a striking incident from April 1995, McArthur Wheeler attempted to rob two banks while believing that lemon juice would render his face invisible to security cameras—an idea inspired by its use in invisible ink. To his astonishment, law enforcement easily identified him from the footage.

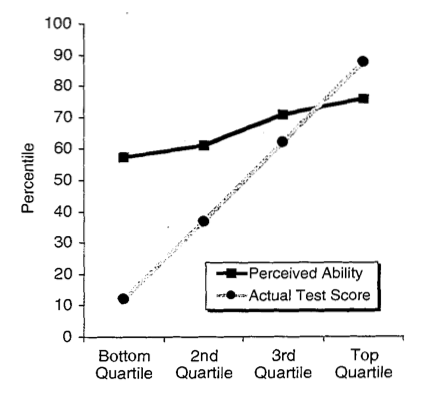

This case of profound misunderstanding intrigued social psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger, who, in 1999, published their influential work titled "Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One’s Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments." They identified the Dunning-Kruger Effect, a phenomenon where individuals lacking knowledge in a domain overestimate their abilities. Interestingly, as individuals gain expertise, they become better at accurately assessing their competence. Those with limited understanding are often unaware of their knowledge gaps.

This pivotal study, featured in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, has since been referenced over 6,000 times in academic literature.

What implications does this have for the assertions we encounter online, especially on platforms like Twitter? Non-experts often exhibit unwarranted confidence in their knowledge within unfamiliar fields. Even esteemed scientists, like Linus Pauling, have fallen victim to the Dunning-Kruger Effect. Pauling, despite lacking training in nutrition, claimed that large doses of Vitamin C could cure the common cold and other ailments—a statement unsupported by substantial research.

This tendency to make unfounded claims is not a sign of lack of intelligence but rather a result of insufficient knowledge in a given area, preventing individuals from recognizing their own limitations.

To better understand our own expertise, consider a subject you are well-versed in, such as brewing coffee or understanding technology. Write down everything you know about it. If it's a technical field, can you explain how its components function? If it involves processes, can you illustrate each step? Such exercises can provide valuable insights into our perceived versus actual knowledge.

The Brain: A Pattern-Seeking Organ

The human brain is primarily designed to identify patterns rather than to crunch numbers or perform complex statistical analysis. It is common for us to misinterpret data. Reflect on times you've made incorrect assumptions based on flawed reasoning.

The Power of Anecdotes

Have you ever encountered a compelling claim supported solely by a personal anecdote? For instance, “Jackfruit cures Athlete’s Foot! It worked for a friend of mine!” Such isolated examples make it nearly impossible to ascertain whether the intervention was responsible for the outcome. Often, conditions may improve naturally over time, complicating matters further.

To genuinely evaluate an effect, rigorous studies comparing the intervention to a placebo are necessary. These randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trials are critical in eliminating biases, ensuring neither the participants nor the researchers know who receives which treatment.

Moreover, a systematic review can synthesize findings from multiple studies, allowing researchers to discern patterns and address discrepancies among the data.

Absolute vs. Relative Risk

Misleading headlines often arise from scientific studies. For example, one might read: "Marshmallows increase the risk of all-cause mortality by 150%." While alarming, this statement lacks context regarding baseline risk. Absolute risk represents the actual probability of an event occurring, while relative risk compares this probability against a baseline.

For instance, if the absolute risk of mortality is 0.0001%, a 150% increase due to marshmallow consumption translates to an absolute risk of 0.00015%. Thus, while relative risk figures may seem significant, they do not provide a complete picture of the actual likelihood of an event.

Common Statistical Misunderstandings

A few common pitfalls include:

- Correlation Does Not Imply Causation: Random correlations can appear misleading. For example, while the number of Nicolas Cage films correlates with drowning deaths, this correlation lacks any causal link.

- Conditional Probability: The likelihood of two events occurring can change based on their relationship. Misinterpretations of conditional probabilities, often seen in legal contexts, can exaggerate guilt. It’s crucial to focus on how evidence relates to the individual rather than the evidence in isolation.

This guide aims to enhance your ability to critically evaluate the information we encounter daily, highlighting the cognitive traps our brains often fall into.

Chapter 2: Exploring Optical Illusions

The first video titled "80 Optical Illusions That Play Tricks on Your Brain" showcases a range of visual phenomena that challenge our perception and understanding of reality.

The second video, "How Optical Illusions Trick Your Brain," delves into the mechanisms behind these fascinating visual tricks, further illustrating how our minds can be deceived.