# The Ingenious Strategies of Plants in Their Battle Against Pests

Written on

Chapter 1: Understanding Plant Defense Mechanisms

In the struggle against insect predators, plants have developed an impressive array of chemical defenses.

Although the world of plants may seem serene compared to our bustling lives, a closer look reveals a different story. These organisms are under constant threat from pests, forcing them to engage in a fight for survival.

Rather than merely enduring these challenges, plants have evolved robust defenses. These include chemical compounds that act as toxins, alert other parts of the plant, and even summon help from external allies. However, this level of defense comes with trade-offs, consuming energy and resources that could be allocated for growth and repair. To optimize their survival, plants must strategically decide when and how to deploy their chemical defenses.

Section 1.1: The Early Warning System

One effective tactic is to postpone the production of chemical defenses until an actual attack occurs. When an insect begins to feed on a leaf, the plant emits volatile compounds that signal nearby parts of the plant and neighboring plants to prepare for defense.

This alert system triggers a chain reaction at the molecular level. It starts with the release of "jasmonate" hormones, which break down specific proteins that inhibit the expression of genes responsible for producing various protective chemicals. By eliminating these inhibitory proteins, plants can activate their defenses.

Additionally, many plants have formed symbiotic relationships with underground fungi. These fungi not only help plants absorb essential nutrients but also facilitate communication between them. Experiments have shown that when aphids infest one plant, connected plants via this fungal network begin to produce defensive compounds, while unconnected ones do not. This underground network acts like a biological Internet, sharing vital information among plants.

Section 1.2: Recruiting Allies

Plants can also conserve energy by enlisting the help of natural predators. They release specific volatile compounds to attract these predators, turning the tide in their favor. For instance, when caterpillars munch on European maize, the plants emit a chemical called β-caryophyllene, which lures parasitic wasps. These wasps lay their eggs inside the caterpillars, ultimately leading to their demise.

Interestingly, the maize also emits this compound underground in response to rootworm attacks, signaling predatory roundworms to come feast on the pests. However, this strategy can backfire; some maize varieties have lost the ability to produce this chemical, making them more susceptible to pests. Restoring this ability in laboratory conditions led to the introduction of pathogenic fungi, presenting plants with a dilemma between maintaining their allies and risking infection.

Chapter 2: Innovative Defense Mechanisms

Description: This video explores the fascinating relationship between plants and their defenses during World War II, highlighting the remarkable adaptations of plants in their struggle for survival.

Description: Judith Sumner discusses the complexities of plants in warfare, showcasing how they adapt to survive in challenging environments.

Section 2.1: Setting Traps

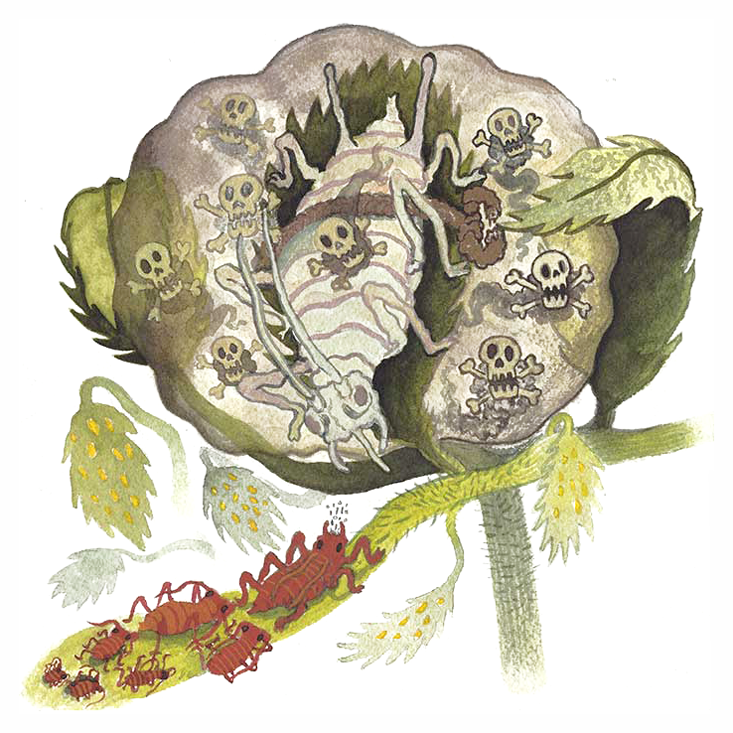

Rather than launching chemical attacks indiscriminately, some plants create elaborate traps for their attackers. For instance, members of the Brassicaceae family (such as broccoli and cabbage) store seemingly innocuous compounds called glucosinolates alongside enzymes known as myrosinase. When a herbivore damages the cell wall, these two components mix, resulting in a toxic reaction that repels the attacker.

These traps are only deployed when they are likely to be effective. The presence of chewing insects prompts the plant to increase glucosinolate production, while sap-sucking insects like aphids do not trigger this response, allowing the plant to conserve resources.

Section 2.2: Mimicking Enemy Signals

Some plants have mastered the art of deception, exploiting the communication methods of their enemies. For example, aphids release a pheromone called β-farnesene when threatened, warning other aphids to flee. To counter this, plants emit β-farnesene during an aphid attack, trying to mimic this distress signal and intimidate the pests.

However, this tactic requires finesse. Many plants release this pheromone continuously, which aphids eventually ignore. The wild potato, however, has developed a unique method by storing the pheromone in specialized bulbs. When an aphid lands and struggles to escape, it breaks these bulbs, releasing the pheromone in short bursts that effectively mimic an alarm signal.

Section 2.3: Healing Wounds

In the aftermath of an attack, plants must quickly address their injuries. They produce a variety of compounds known as green leaf volatiles that act as antiseptics, safeguarding damaged tissues from infection. These volatiles are responsible for the fresh-cut grass aroma and send distress signals to nearby plants.

Plants also generate traumatic acid, known as the "wound hormone," which encourages cell division to mend injuries. This self-repair process begins almost immediately after an attack, allowing plants to simultaneously fend off invaders while healing.

As the evolutionary battle between plants and insects continues, each side adapts to gain the upper hand. Insects are evolving counter-defenses, prompting plants to innovate new strategies. This ongoing struggle resembles a Red Queen's race, where both parties must exert constant effort just to maintain their status.

Mike Newland is a post-doctoral research assistant at the University of East Anglia, focusing on the interactions between the biosphere and atmosphere.